The government is being accused of using national security as an excuse to withhold crucial historical documents from academics researching British spy agencies.

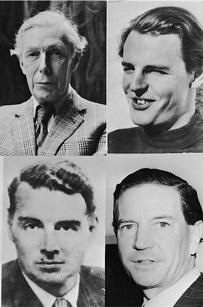

One historian has now obtained legal advice that suggests the government is breaking freedom of information laws by not releasing Cabinet Office files he needs for his research into Anthony Blunt, one of the Cambridge Five spies who were revealed to have betrayed their country to the Soviet Union.

The claim has been accompanied by a barrage of criticism regarding the government’s retention of files from other historians who have told BuzzFeed News their efforts to access historical records have been constantly frustrated by officials. It will add to the growing sense of unrest around how the government administers the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act.

Anthony Lownie, whose previous book, Stalin’s Englishman: The Lives of Guy Burgess, describes the life of another of the Cambridge spies, applied under Freedom of Information laws for the Blunt files last year but his application was rejected.

After Lownie appealed the FOI rejection, he was told the files would be “opened at the National Archives” later in 2015, but they did not appear there. He threatened to write to his MP and was eventually told that the files had not been made available because they were “part of a larger process” of making files available to the National Archives.

He then took legal advice and was told that he had been given an “expectation’” of transfer by the end of 2015 and therefore the Cabinet Office could be legally challenged for breaching FOI legislation.

Andrew Lownie

He told BuzzFeed News: “This particular flouting of FOI legislation doesn’t surprise me because it is commonplace throughout government though the Cabinet Office, supposedly responsible for supervising FOI across Whitehall, are one of the worst offenders. The government is withholding records going back to the Victorian period. How can historians write accurate history if the documents are not made available?”

He says that his efforts to research Burgess have also been frustrated by the way the government “brazenly” flouts both FOI and the Public Records Act, which requires government documents to be placed in the National Archives within 20 years, unless they pose a threat to national security.

He said: “This is not just a matter for historians but any concerned citizen. Making government records publicly available is an essential part of any democracy. It is perhaps not surprising therefore that trust in our institutions is at such an all time low when they so flagrantly ignore both FOI legislation and the Public Records Act.”

Earlier this month, Lownie set out in a blog what he described as the “Kafkaesque journey” he had taken to secure government information about Burgess. He said he’d had “particular difficulty” with the Cabinet Office – the government department responsible for the implementation of FOI across government.

He cited a number of other government “tricks” that prevented him accessing files. They ranged from delaying their answers to requests to simply not answering them at all, and also, in his words, “being difficult”.

He wrote: “One of my recent refusals was on the grounds the document gave away surveillance techniques – it is over sixty years old.” He cited another example: “ I was asked to obtain a death certificate for a spy born in 1908 who has several online obituaries in national newspapers to prove that he wasn’t alive at [the age of] 106.”

Lownie points out the Foreign Office has 600,000 files at a high security facility shared with MI6 and MI5, which are only known about because they came to light during a court case – they will, according to the Government, take “years” to review for release, yet they date back to the Victorian period.

Dr Rory Cormac, a professor of international relations at the University of Nottingham, told BuzzFeed News that he’d faced particular problems with FOI: “They just stonewall,” he said. “I’ve had 18 month-long battles to get papers relating to MI6 so I’ve had to pick my battles carefully.”

He told BuzzFeed News that last year he’d requested files about the Committee on Communism (Overseas), a body overseeing anti-communist policy in the 1950s. Some of its files were already released but others were not. His FOI request was rejected last July by the Cabinet Office, although he says that the department had informally told a colleague that they were likely to be released. He’d appealed in September but it was only last week he was finally told they had been wrong to deny him one file.

However, instead of giving him a copy Cormac said the department had decided to withhold it on other (non-security) grounds, arguing that it was in the process of transferring it to the National Archives and so to give him a copy would breach section 22(1) of the FOI act protecting "information intended for future publication”.

The National Archives, Kew.

He said: “The catch is that they will not transfer the file to the archives until 31 December 2016. This is a deliberate ploy to stop me having it as they know full well that whatever research project I'm on will be finished by then.”

He added that he’d struggled to get hold of other intelligence documents relating to anti-communist operations in the 1950s and was bemused as to why: “They don’t even contain operational detail – they’re policy wonks discussing potential operational detail, he said.”

Cormac said he’d told off record by government staff that many of the problems were due to cuts in their departments: “It’s often just one poor man or woman on their own,” he said. He added that the 2013 announcement by the government that historical papers have to be released after 20 years rather than 30 had created a huge added workload.

Another historian who has written at length about the intelligence services, Nigel West (the pen name of former MP Rupert Allason), told BuzzFeed News he remembered having discussions with government officials prior to the introduction of the Freedom of Information Act in which they said they couldn’t believe there would ever be declassification.

“MI5 employs retirees to declassify the documents, but they don’t know how to redact,” he said. This, he felt, lead to them erring too far on the side of caution. He said it was “impossible to put the genie of declassification back in the bottle”. He said: “You can see the difficulty – it’s difficult to make records public when you’ve promised people that compromising information won’t be made public in their lifetimes, or even, in some cases, in their grandchildren’s lifetimes.

“It’s hard [for the intelligence services] to get people to cooperate when you know the records might well end up in Kew,” he added. There are clear dangers: West described one occasion when he was writing about the history of MI6’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) operations and found a collection of documents in the National Archives that related to the finances of a worldwide network of Passport Control Officers – which was the cover for SIS.

This gave him a matrix that meant he was able to piece together the names of former SIS members – many of whom were still alive at the time, and who he contacted and spoke to for his book. After it was published, the papers were removed from the National Archives.

He pointed out it’s not just the British government that has struggled with declassification. He said that one senior American security official had told him more CIA officers were engaged in declassification than counter-terrorism prior to 9/11.

Two other historians - both of whom Andrew Lownie represents in his role as a literary agent – told BuzzFeed News about their struggles with FOI. Glyn Gowans, who has written a biography of Prince George, the Duke of Kent, told BuzzFeed News that his efforts to dig up documents about a royal visit to New York in 1942 had been stymied by a “signed instrument” brought in by former justice secretary Chris Grayling in 2011.

Keystone / Getty Images

The instrument effectively enables Whitehall to retain any 'historical record' (currently means any document pre-dating 1991) relating to intelligence services including MI6, MI5 and GCHQ on the grounds of national security. Gowans is currently challenging the Foreign Office over the retention of this document.

Lownie told BuzzFeed News: “The justification seems to be that any records relating to intelligence, whether sensitive or not, can be retained under a blanket exemption signed in 2011. No one seems prepared to hold government departments to account. Not politicians, not academia, not the media, not the Advisory Committee on Records at the National Archives. It’s a scandal and more reminiscent of a banana republic.”

Another author represented by Lownie, David McClure, who last year published a book about the royal finances and how the Windsors pass on their wealth, said that he had tried to acquire documents relating to the Civil List for the new Queen in 1952, but had been told they were to be closed for 100 years.

He said: “When state documents are now governed by the 20 year rule why do we have to wait 100 years to see the 1952 Civil List papers setting out the details of the new Queen’s state funding by Churchill’s government? Why are members of the royal family granted special privileges when it comes to access to government papers about their state funding? What are they hiding?”

He also told BuzzFeed News that he had struggled to get hold of a 45-year-old cache of documents in the National Archives relating to the Civil List, which had been “temporarily retained” by the Treasury. He wrote to the department in 2011, but never received a reply. He said: “One of the most effective ways for Whitehall to stifle valid journalistic or historical inquiry is to do nothing. The reason is that you just wait not knowing that they are not processing your request. If I had known they would do nothing, I would have put in an FOI request.”

He has now done so, but has yet to acquire the documents. In his book, he writes: “A cynic might judge that they had decided to hammer an extra nail into the lid of the coffin after the thirty year rule had let in too much daylight."

A Cabinet Office spokesperson said, "This Government is committed to being the most transparent ever and we are publishing unprecedented amounts of information. The Cabinet Office is working hard to ensure that files are transferred as soon as possible to The National Archives as we move from a 30 year to 20 year rule."

Disclosure: in his role as a literary agent, Lownie has also represented the author of this post.

The Government Is Stopping Us Writing About Spies And The Royal Family, Say Historians