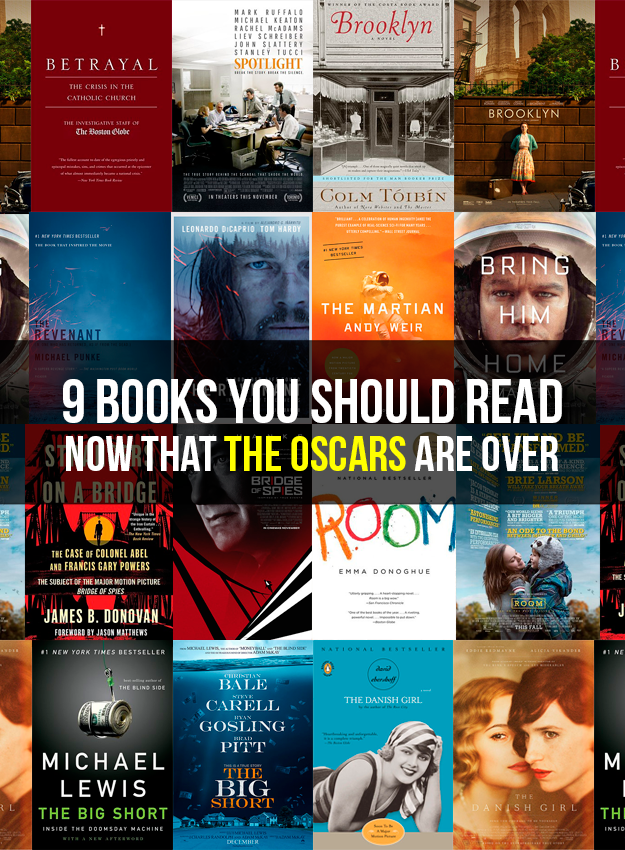

It was an acquaintance’s idea to go there, to James Baldwin's house. He knew from living in Paris that Baldwin's old place, the house where he died, was near an elegant, renowned hotel in the Cote D'Azur region of France. He said both places were situated in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, a medieval-era walled village that was scenic enough to warrant the visit. He said we could go to Baldwin's house and then walk up the road for drinks at the hotel bar where the writer used to drink in the evening. He said we would make a day of it, that I wouldn’t regret it.

For the first time in my life I was earning a bit of money from my writing, and since I was in London anyway for work and family obligations I decided to take the train over to Nice to meet him. But I remained apprehensive. Having even a tiny bit of disposable cash was very new and bizarre to me. It had been years since I had I bought myself truly new clothes, years since going to a cash machine to check my balance hadn’t warranted a sense of impending doom, and years since I hadn’t on occasion regretted even going to college, because it was increasingly evident that I would never be able to pay back my loans. There were many nights where I lay awake turning over in my mind the inevitable — that soon Sallie Mae or some faceless, cruel moneylender with a blues song–type name would take my mother’s home (she had co-signed for me) and thus render my family homeless. In my mind, three generations of progress would be undone by my vain commitment to tell stories about black people in a country where the black narrative was a quixotic notion at best. If I knew anything about being black in America it was that nothing was guaranteed, you couldn’t count on anything, and all that was certain for most of us was a black death. In my mind, a black death was a slow death, the accumulation of insults, injuries, neglect, second-rate health care, high blood pressure, and stress, no time for self-care, no time to sigh, and, in the end, the inevitable, the erasing of memory. I wanted to write against this, and so I was writing a history of the people I did not want to forget. And I loved it; nothing else mattered, because I was remembering, I was staving off death.

So I was in London when a check with four digits and one comma hit my account. It wasn’t much but to me it seemed enormous. I decided if I was going to spend any money, something I was reluctant, if not petrified, to do, at the very least I would feel best about spending it on James Baldwin. After all, my connection to him was an unspoken hoodoo-ish belief that he had been the high priest in charge of my prayer of being a black person who wanted to exist on books and words alone. It was a deification that was fostered years before during a publishing internship at a magazine. During the lonely week I had spent in the storeroom of the magazine’s editorial office organizing the archives from 1870 to 2005, I had found time to pray intensely at the altar of Baldwin. I had asked him to grant me endurance and enough fight so that I could exit that storeroom with my confidence intact. I told him what all writers chant to keep on, that I had a story to tell. But later, away from all of that, I quietly felt repelled by him — as if he were a home I had to leave to become my own. Instead, I spent years immersing myself in the books of Sergei Dovlatov, Vivian Gornick, Henry Dumas, Sei Shogonan, Madeline L’Engle, and Octavia Butler. Baldwin didn’t need my prayers — he had the praise of the entire world.

I still liked Baldwin but in a divested way, the way that anyone who writes and aspires to write well does. When people asked me my opinion on him I told them the truth: that Baldwin had set the stage for every American essayist who came after him with his 1955 essay collection Notes of a Native Son. One didn't need to worship him, or desire to emulate him, to know this and respect him for it. And yet, for me, there had always been something slightly off-putting about him — the strangely accented, ponderous way he spoke in the interviews I watched; the lofty, “theatrical” way in which he appeared in "Good Citizens," an essay by Joan Didion, as the bored, above-it-all figure that white people revered because he could stay collected. What I resented about Baldwin wasn’t even his fault. I didn’t like the way many men who only cared about Ali, Coltrane, and Obama praised him as the black authorial exception. I didn’t like how every essay about race cited him. How they felt comfortable , as he described it, talking to him (and about him) “absolutely bathed in a bubble bath of self-congratulation.”

James Baldwin and my grandfather were four years apart in age, but Baldwin, as he was taught to me, had escaped to France and avoided his birth-righted fate, whereas millions of black men his age had not. It seemed easy enough to fly in from France to protest and march, whereas it seemed straight hellish to live in the States with no ticket out. It seemed to me that Baldwin had written himself into the world — and I wasn’t sure what that meant in terms of his allegiances to our interiors as an everyday, unglamorous slog.

So even now I have no idea why I went. Why I took that high-speed train past the sheep farms and the French countryside, past the brick villages and stone aqueducts, until the green hills faded and grew into Marseille's tall, dusky pink apartments and the bucolic steppes gave way to blue water where yachts and topless women with leather for skin were parked on the beaches.

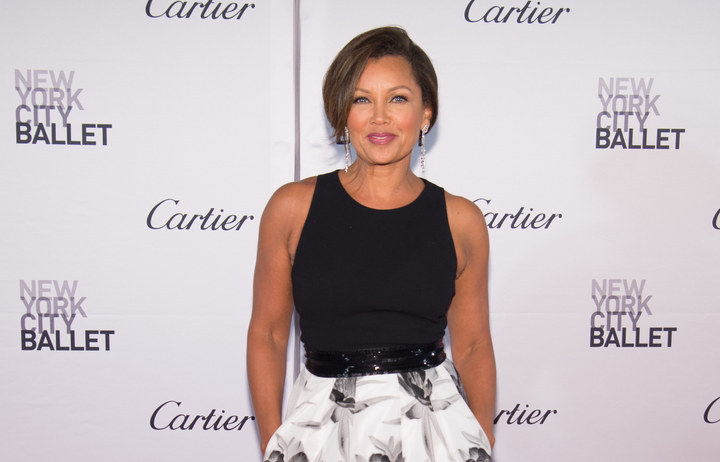

James Baldwin in Paris, October 1975.

Sophie Bassouls / Corbis

It was on that train that I had time to consider the first time Baldwin had loomed large for me. It had occurred 10 years earlier, when I was accepted as an intern at one of the oldest magazines in the country. I had found out about the magazine only a few months before. A friend who let me borrow an issue made my introduction, but only after he spent almost 20 minutes questioning the quality of my high school education. How could I have never heard of such an influential magazine? I got rid of the friend and kept his copy.

During my train ride into Manhattan on my first day, I kept telling myself that I really had no reason to be nervous; after all, I had proven my capability not just once but twice. Because the internship was unpaid I had to decline my initial acceptance to instead take a summer job and then reapplied later. When I arrived at the magazine’s offices, the first thing I noticed was the stark futuristic whiteness. The entire place was a brilliant white, except for the tight, gray carpeting.

The senior and associate editors’ offices had sliding glass doors and the rest of the floor was divided into white-walled cubicles for the assistant editors and interns. The windows in the office looked out over the city, and through the filmy morning haze I could see the cobalt blue of one of the city’s bridges and the water tanks that spotted some of the city’s roofs. The setting, the height, and the spectacular view were not lost on me. I had never before had any real business in a skyscraper before.

Each intern group consisted of four people; my group also included a recent Brown grad, a hippie-ish food writer from the West Coast, and a dapper Ivy League sort of mixed-race Southeast Asian descent. We spent the first part of the day learning our duties, which included finding statistics, assisting the editors with the magazine's features, fact-checking, and reading submissions. Throughout the day various editors stopped by and made introductions. Sometime after lunch the office manager came into our cubicle and told us she was cleaning out the communal fridge and that we were welcome to grab whatever was in it. Eager to scavenge a free midday snack, we decided to take her up on the offer. As we walked down the hall the Princeton grad joked that because he and I were the only brown folks around we should be careful about taking any food because they might say we were looting. I had forgotten about Hurricane Katrina, the tragedy of that week, during the day’s bustle, and somehow I had also allowed the fact that I am black to fade to the back of my thoughts, behind my stress and excitement. It was then that I was smacked with the realization that the walls weren’t the only unusually white entities in the office — the editorial staff was strangely all white as well.

Because we were interns, neophytes, we spent the first week getting acquainted with each other and the inner workings of the magazine. Sometime towards the end of my first week, a chatty senior editor approached me in the corridor. During the course of our conversation I was informed that I was (almost certainly) the first black person to ever intern at the magazine and that there had never been any black editors. I laughed it off awkwardly only because I had no idea of what to say. I was too shocked. At the time of my internship the magazine was more than 150 years old. It was a real Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner moment. Except that I, being a child of the '80s, had never watched the film in its entirety, I just knew it starred Sidney Poitier as a young, educated black man who goes to meet his white wife’s parents in the 1960s.

When my conversation with the talkative editor ended I walked back to my desk and decided to just forget about it. Besides, I reasoned, it was very possible that the editor was just absent-minded. I tried to forget it myself but I could not, and finally I casually asked another editor if it was true. He told me he thought there had been an Algerian-Italian girl many years ago, but he was not certain if she really "counted" as black. When I asked how that could be possible, I was told that the lack of diversity was due to the lack of applications from people of color. As awkward as these comments were, they were made in the spirit of oblivious commonwealth. It was office chatter meant to make me feel like one of the gang, but instead of comforting my concerns it made me feel like an absolute oddity.

On good days, being the first black intern meant doing my work quickly and sounding extra witty around the water cooler; it meant I was chipping away at the glass ceiling that seemed to top most of the literary world. But on bad days I gagged on my resentment and furiously wondered why I was selected. I became paranoid that I was merely a product of affirmative action, even though I knew wasn’t. I hadn't mentioned my race in either of my two accepted applications. Still, I never felt like I was actually good enough. And with my family and friends so proud of me, I felt like I could not burst their bubble with my insecurity and trepidation.

So when I was the only intern asked by a top editor to do physical labor and reorganize all of the old copies of the magazine in the freezing, dusty storeroom, I fretted in private. Was I asked because of my race or because that was merely one of my duties as the intern-at-large? There was no way to tell. I found myself most at ease with the other interns and the staff that did not work on the editorial side of the magazine: the security guards, the delivery guys, the office manager, and the folks at the front desk. Within them the United Nations was almost represented. With them, I did not have to worry that one word pronounced wrong or one reference not known would reflect not just poorly on me but also on any black person who might apply after me.

Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah

I also didn’t have to worry about that in that storeroom. I vexingly realized three things spending a week in the back of that dismal room. That yes, I was the only intern asked to do manual labor, but I was surrounded by 150 years of the greatest American essays ever written, so I read them cover to cover. And I discovered that besides the physical archives and magazines stored there, the storeroom was also home to the old index card invoices that its writers used to file. In between my filing duties, I spent time searching those cards, and the one that was most precious to me was Baldwin's. In 1965, he was paid $350 for an essay that is now legend. The check went to his agent's office. There was nothing particularly spectacular about the faintly yellowed card except that its routineness suggested a kind of normalcy. It looped a great man back to the earth for me. And in that moment, Baldwin’s eminence was a gift. He had made it out of the storeroom. He had taken a steamer away from being driven mad from maltreatment. His excellence had moved him beyond the realm of physical labor. He had disentangled himself from being treated like someone who was worth-less or questioning his worth. And better yet, Baldwin was so good they wanted to preserve his memory. Baldwin joined the pantheon of black people who were from that instructional generation of civil rights fighters, and I would look at that card every day of my week down there.

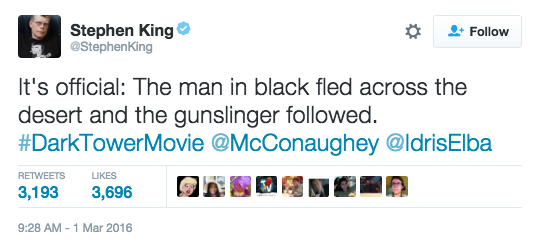

James Baldwin in New York City on May 31, 1974.

Waring Abbott / Getty Images

What makes us want to run away? Or go searching for a life away from ours? The term "black refugees" applies most specifically to the black American men and women who escaped in 1812 to the British navy’s boats and were later taken to freedom in Nova Scotia and Trinidad, but don’t many of us feel like black refugees. Baldwin called these feelings, the sense of displacement and loss that many Black Americans ponder, the “heavy” questions, and heavy they are indeed. Sometime in early '50s, after being roughed up and harassed by the FBI, James Baldwin realized that while he “loved” his country, he “could not respect it.” He wrote that he “could not, upon my soul, be reconciled to my country as it was.” To survive he would have to find an exit. On the train to Baldwin’s house I thought more about that earlier generation and about the seemingly vast divide between Baldwin and my grandfather. They had very little in common, except they were of the same era, the same race, and were both fearless men, which in black America actually says a lot. Whereas Baldwin spent his life writing against a canon, writing himself into the canon, a black man recording the Homeric legend of his life himself, my grandfather simply wanted to live with dignity.

It must have been hard then to die the way my grandfather did. I imagine it is not the ending that he expected when he left Louisiana and moved to Watts — to a small, white house near 99th Street and Success Avenue. After his death, I went back to the house in Watts that he had been forced to return to, broke and burned out of his home, and gathered what almost 90 years of black life in America had amounted to for him: a notice saying that his insurance claim from the fire had been denied, two glazed clay bowls, and his hammer (he was a carpenter). My grandfather had worked hard but had made next to nothing. I took a picture of the wall that my grandfather built during his first month in LA. It was old, cracked, jagged, not pretty at all, but at the time, it was the best evidence I had that my grandfather had ever been here. And as I scattered his ashes near the Hollywood Park racetrack, because he loved horses and had always remained a country boy at heart, I realized that the dust in my hands was the entirety of my inheritance from him. And until recently, I used to carry that memory and his demand for optimism around like an amulet divested of its power, because I had no idea what to do with it. What Baldwin understood, and my grandfather preferred not to focus on, is that to be black in America is to have the demand for dignity be at absolute odds with the national anthem.

From the outside, Baldwin’s house looks ethereal. The saltwater air from the Mediterranean acts like a delicate scrim over the heat and the horizon, and the dry, craggy yard is wide and long and tall with cypress trees. I had prepared for the day by watching clips of him in his gardens. I read about the medieval frescos that had once lined the dining room. I imagined the dinners he had hosted for Josephine Baker and Beauford Delaney under a trellis of creeping vines and grape arbors. I imagined a house full of books and life.

I fell in love with Baldwin all over again in France. There I found out that Baldwin didn’t go to France because he was full of naïve, empty admiration for Europe; as he once said in an interview: “If I were twenty-four now, I don’t know if and where I would go. I don’t know if I would go to France, I might go to Africa. You must remember when I was twenty-four there was really no Africa to go to, except Liberia. Now, though, a kid now . . . well, you see, something has happened which no one has really noticed, but it’s very important: Europe is no longer a frame of reference, a standard-bearer, the classic model for literature and for civilization. It’s not the measuring stick. There are other standards in the world.”

Baldwin left the States for the primary reason that all emigrants do — because anywhere seems better than home. This freedom-seeking gay man, who deeply loved his sisters and brothers — biological and metaphorical — never left them at all. In France, I saw that Baldwin didn’t live the life of a wealthy man, but he did live the life of man who wanted to travel, to erect an estate of his own design, and write as an outsider, alone in silence. He had preserved himself.

Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah

![]()

![]()

Why I’ve Stopped Giving And Asking For Advice